The Making of ‘Pathways to Freedom’

Posted by Aug 15, 2019

Julia Vogl

When a Jewish organization wants to make an artwork accessible to all—it has to reach out to all in the making of the work. That’s what I and the Jewish Arts Collaborative, a Boston arts organization, did together to explore the meaning of the Passover holiday.

To me, the themes of Passover were already universal—leaving oppression, seeking a new start, ending up in limbo for years as you find a new home. The Exodus story is the story for many refugees today, one of how seeking freedom is about liberation but with a responsibility, too.

Because the Pathways to Freedom artwork was going to surround the Soldiers and Sailors Civil War monument on Boston Common, at the city center, I wanted to be as inclusive as possible in making the work.

To me, the themes of Passover were already universal—leaving oppression, seeking a new start, ending up in limbo for years as you find a new home. The Exodus story is the story for many refugees today, one of how seeking freedom is about liberation but with a responsibility, too.

So, I created a pop-up cart and with the JArts team and a band of volunteers, we travelled across the Boston region. Our mission: to engage people on the subject of freedom and immigration. We went to 27 different locations, engaging 1,800 individuals in sharing their stories, collecting data, and recording audio interviews. Each participant answered multiple choice questions and made a pin based on their answers.

The Process

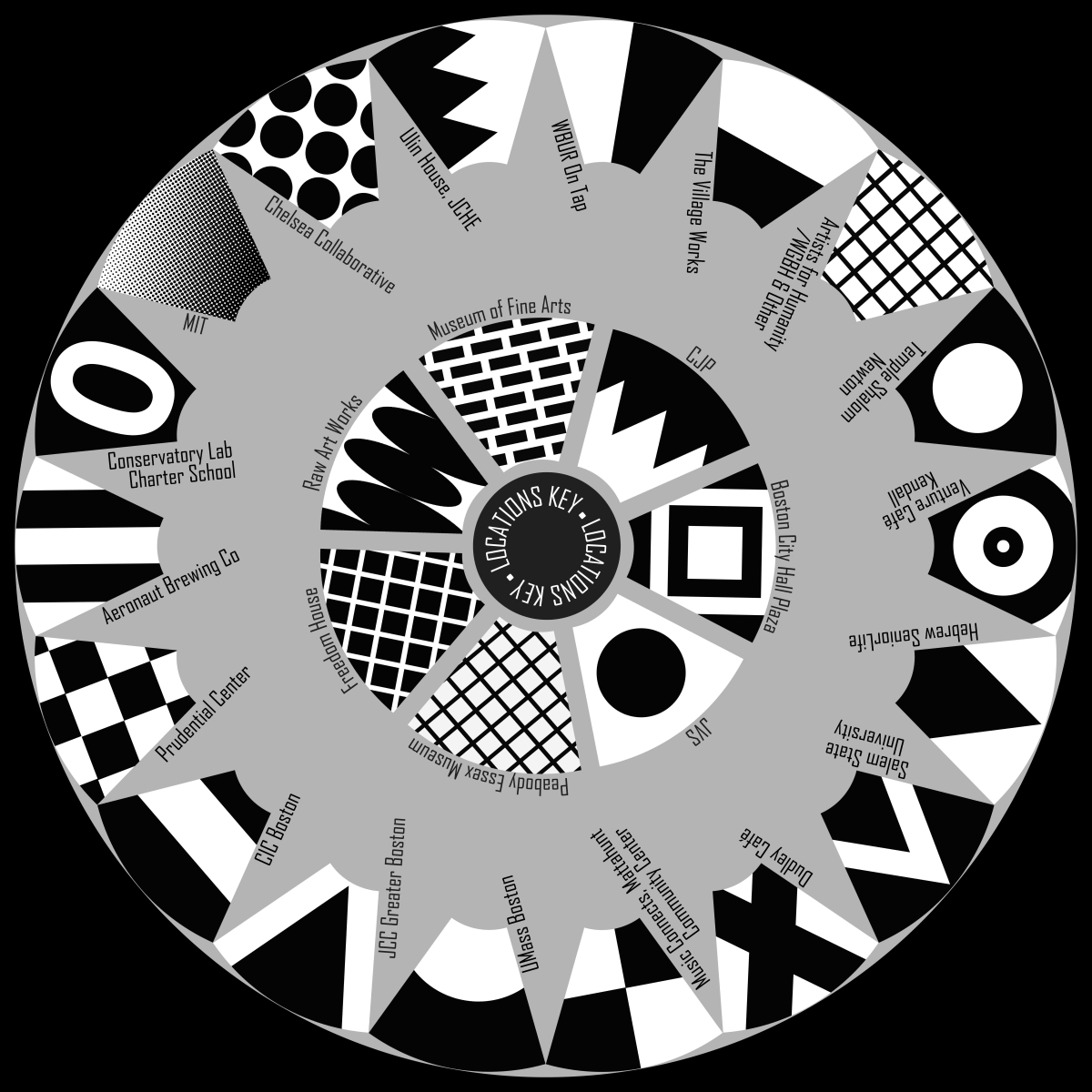

1) Each community location was assigned a different pattern for the pin; here are all the various locations we engaged. We traveled from City Hall and MIT to the Museum of Fine Arts, the Mattahunt Community Center, and beyond.

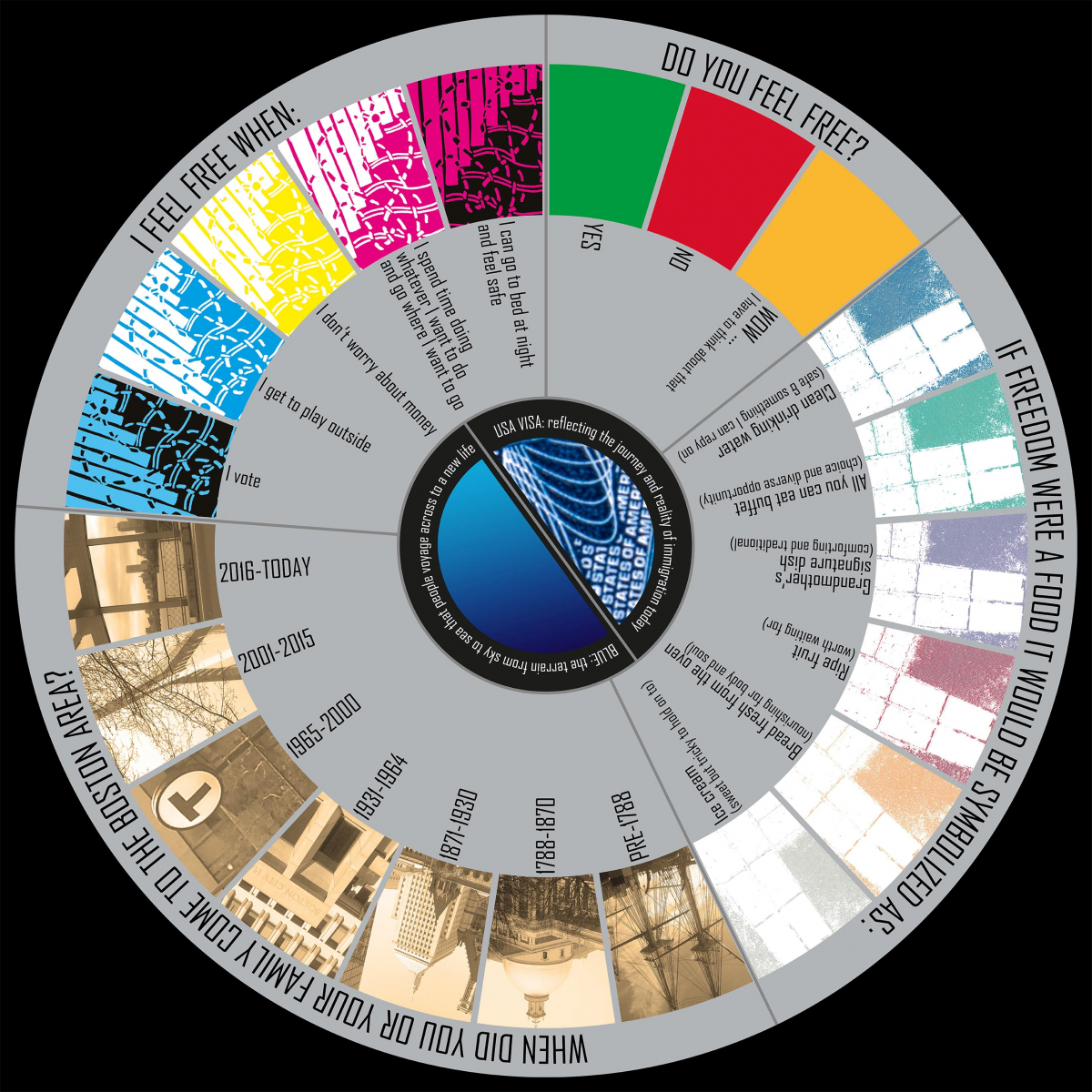

2) Every participant was asked four multiple choice questions. Here is a visual key of the imagery associated with their responses.

3) At each site, I erected my cart, which had two iPads and colorful stickers to place on the pins. Here at City Hall you can see the stand, and how people could engage.

4) Sometimes we had just one person on an iPad answering questions, and sometimes we had a whole family or community involved, discussing the options and making choices together.

5) After making their choices, everyone made a pin that they could keep. Here is a collage of some of the 2,000 people we engaged and the pins they made.

6) The project included participants’ stories, their answers to the questions we asked, a digital version of the pins they made, and a real pin that they walked away with. The final artwork was a 6,000 square foot floor sidewalk made of vinyl, containing enlarged versions of the created pins, connecting people who live across the region in one place for three weeks.

7) Once the work was up, participants could return and find their enlarged pin on the mural. Some had audio interviews included and could find their pin as well as a key word that was associated with their story. Visitors to the artwork could also listen to the audio recordings using their cell phones.

The Lessons

The Lessons

While the work was not an assessment on U.S. immigration policy, the work invoked many personal stories, passionate and different political views, and illustrated the diversity of the city as well as huge commonalities. Participants were invited back to find their pin—and see where they fit in among 2,000 others, to discover what they share with strangers and how they differ. Ultimately, the legacy of the project sits on their chest, their backpacks, or lapels—the pins continue to be worn, making every participant a storyteller for the legacy of the project, and furthering conversations in other communities about freedom and immigration. That was very rewarding: to know that a specific outreach has now grown much larger and connected others.

This post is part of The “Public” In Public Art: Community Engagement Stories From The 2019 PAN Year In Review blog salon.